Commercial Banking in Mexico

Under the vigilant eye of Bank of Mexico governor, Agustin Carstens, the nation’s banks boast sky-high Tier 1 capital ratios compared with most countries and will meet the latest Basle standards for integrity and robustness with relative ease.

Largely unaffected by the financial crisis, the financial sector – particularly commercial banking in Mexico – is growing steadily on the back of an economy expanding at more than four times the rate of Europe and significantly faster than that of America. Corporate lending hardly slowed between 2008-2010, as evidenced by a dynamic M&A market that has lately seen some of the biggest deals in the world and by the growing presence of a number of international institutions anxious to exploit opportunities in Mexico.

Encouraged by the government, household lending is also deepening through a home-grown, far-reaching network that comprises branch banking, agent arrangements based in retail chains, Mexico-style savings and loan institutions, mobile-phone banking and microfinance.

These developments are underpinned by the depth and discipline of Mexico’s money markets that have attracted global interest. As the international investment community gains confidence in the government’s management of the broader economy, it’s playing a growing role in the development of one of the world’s most exciting emerging nations.

Regulatory framework

The “peso crisis” that hit Latin America in 1995 taught Mexico lessons it never forgot. As a result the nation boasted one of the most robust financial sectors in the world when the latest crisis arrived in late 2008. Commercial banking in Mexico was highly capitalised, with banks far above their counterparts in America. Debt provisioning ratios were some of the most cautious in the world and liquidity was high. The large and complex off-balance sheet activities that nearly destroyed several global banks were notably absent and the cross-border linkages that contaminated other financial sectors were limited. Household debt was low by the standards of most western countries.

The result is that the economy as a whole recovered from the turmoil faster than almost any other country, and as such commercial banking in Mexico has performed well comparatively as a sector. Christine Lagarde, managing director of the International Monetary Fund, has singled out Mexico as a shining example of prudent economic and financial management. Along with Brazil and Peru, it “can provide some lessons to the advanced countries—such as saving for a rainy day, and making sure that risks in the banking system are under control,” she approved.

Unsurprisingly, the latest IMF report on Mexico effectively gives the financial sector a nearly five-star rating, citing capital adequacy ratios and liquidity indicators that actually exceed pre-crisis levels. Indeed Mexico’s main regulator, the National Banks and Securities Commission (CNBV), was one of the few banking watchdogs to welcome the significantly higher capital requirements required last year under Basle III. “The new agreements do not represent the kind of comprehensive changes that banks in some countries will have to make”, the regulator said.

Attracted by an increasingly affluent population and a growing commercial sector, international banks have moved into Mexico in the last few years. A wave of mergers and acquisitions has added depth and international experience, and strengthened the money markets that underpin a liquid and stable financial sector. One result is that the provision of credit to the private sector hardly slackened in the crisis, slowing only slightly between 2009-2010 because of reduced demand rather than any reluctance by the banks to lend. Commercial lending has expanded steadily throughout 2011, and as such commercial banking in Mexico has benefited.

Popular financial instruments

Mexico’s historically close links with the United States have strongly influenced its financial markets. For instance, Americans have long invested in American Depository Receipts that allow them to trade in Mexican securities and in mutual funds, some of which are listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Although not guaranteed like the banks, mutual funds are extremely diverse with strategies ranging from “conservative” to “aggressive”.

The pool of zero-coupon federal treasury certificates known as cetes has deepened greatly in the last few years, particularly as the treasuries of foreign banks and corporates become more confident in the government’s ability to control inflation, which has added to make commercial banking in Mexico more competitive. Like other sovereign issues, the yield on cetes depends essentially on how well the economy is managed.

A private institution governed by the Mexican Securities Market Act, the Mexican stock exchange allows any individual, foreign or local, to invest in its instruments and securities, adding flexibility to commercial banking in Mexico. The board boasts about 250 issuers but only 40 companies are actively traded. Like ADRs, cetes and other instruments, securities on the exchange can be acquired through authorised Mexican brokerage houses on commissions ranging between 1-1.5 per cent of the trade.

The fixed-interest market is disciplined and organised. At 12pm every Friday the Bank of Mexico releases details of the following week’s sovereign bond sales in terms of exact instrument, maturity and amount. Besides the cetes, the government’s fixed-rate Mbonos development bonds are regarded as an important instrument because they reflect the ability to control inflation and sovereign risk. Also, UDIbonos are considered ideal for institutional investors such as insurance companies, pension and retirement funds. An active secondary market for UDIbonos means they can be freely traded before maturity.

Driven partly by the investment decision of the one million American expatriates living in Mexico – the largest number of US citizens living in a single foreign country, there’s an established network of settlement and custody services to meet the needs of investors in financial and other securities.

Personal finance

With a population of 113 million, the country is hungry for all kinds of retail banking services from mortgages and consumer loans to credit cards and bill payments. It follows that the commercial banking in Mexico is flourishing. Although sophisticated retail products are available in the cities, many Mexicans live in remote areas beyond the reach of ordinary branch banking – for instance, less than half of adults have a cheque account – and the government and financial industry are working together to fill the gap.

With an estimated 90 million cellphone users, mobile banking is taking off, and commercial banking in Mexico has thrived in response to the new market. Figures released in mid-2011 unveiled that the number of mobile phones had reached almost five times that of fixed telephone lines. Seeing the opportunities, the government approved the provision of mobile banking services to conduct basic transactions and the commercial banking sector is poised to roll out a range of products. The CNBV expects mobile banking to expand rapidly from 2012.

The provision of agent-based banking services is also encouraged by the Bank of Mexico to extend the reach of financial products. “Retail stores can facilitate the population’s access to basic financial transactions, such as deposits, withdrawals and bill payments,” points out deputy governor Manuel Sanchez. Agent arrangements are considered valuable in communities too remote for branch banking at the moment.

The rapid roll-out of ATMs is also extending the reach of commercial banking in Mexico, with units being installed on a daily basis in nationwide chains such at OXXO, the country’s largest convenience store. The investment is underpinned by companies such as American group Cardtronics, the world’s biggest owner of ATMs that is working through partnerships with retailers and banks.

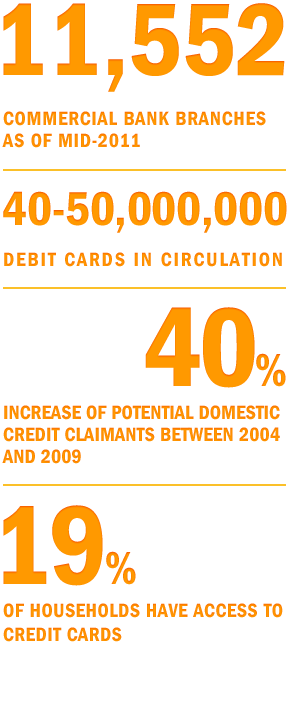

With average household debt including mortgages sitting at just 20 percent of disposable income and shorter-term consumer credit at seven percent, Mexicans remain cautious borrowers. For instance, debit cards greatly outnumber credit cards, with 40 – 50 million of the former in circulation.

The historic savings and loan sector is particularly active, especially for small borrowers, with some 620 societies of widely differing sizes holding over $5.9bn in collective assets. Micro-financing, one of the functions of the S&L sector, is seen as particularly valuable in developing entrepreneurs. The network of “non-bank banks” and other niche financial intermediaries is a long-standing feature of Mexico. These sofomes – multiple-purpose financial institutions – and sofipos – popular financial institutions – complement the main branched institutions by making basic financial services accessible in previously unbanked areas. With more competition in the area, commercial banks in Mexico have raised the standard in product delivery.

Looking ahead, the Bank of Mexico has encouraged commercial banks to lend more than they currently do, albeit under strict guidelines, a task that banks such as Banorte are happy to tackle. “Perhaps the most crucial task for the financial system is to increase its scale and scope,” explains deputy governor Sanchez.

Corporate finance

The rapid inflows of capital have greatly boosted Mexico’s financial markets in the last two years. Regarded as a safe haven because of the appreciation of the peso and a strong sovereign credit rating, the markets saw portfolio inflows reach a record $37bn in 2010, with $23bn of that invested in government bonds. The inclusion of Mexico in the global bond index (WGBI) has also served to attract long-term institutional investors. As a result, Mexico boasts a mature swaps, futures and forwards market. Forward rate agreements are the most-used derivative instruments while interest rate swaps are the most commonly traded financial ones. To date, hedge funds are not licensed to operate in Mexico but the CNBV is exploring a structure for them under international guidelines.

The relatively free availability of capital has energised the mergers and acquisitions market. Supported by unexpectedly high corporate profits, private equity funding and bank lending, M&A activity exceeded expectations with deals being done in telecommunications, food and beverage, energy, automotive and pharmaceuticals among other sectors. Tapping the expertise of an extensive and experienced domestic legal infrastructure, McDonalds, Anheuser-Busch, Grupo Televisa and other global brands have jumped into the market.

Indeed of the total $93bn in reported M&A deals done in the emerging markets of Brazil, Mexico and China in 2010, Mexico claimed the lion’s share, according to Mergers and Acquisitions Review. It boasted $39.6bn in deals, more than for the whole of Europe.

America Movil’s $25.7bn acquisition of Mexico City-based Carso Global Telecom was the second-biggest transaction of 2010.

Investment funds in Mexico play an increasingly important role in these transactions and will continue to do as “an increase in M&A activity is expected to occur in the years to come”, concludes the publication.

Meantime it’s done no harm to the M&A boom in Mexico that it’s raising its general commercial standards. In the global “ease of doing business” rankings, the country lies 53rd, well ahead of the regional Latin American average of 95th.

Standards in the region

The country is now reaping the rewards of the prudent and astute management of the financial system and Mexico’s commercial banking platform. The OECD estimates that GDP will grow by 4.5 percent during 2011. Bank of Mexico’s governor Agustin Carstens gets much of the credit for this, with the numbers telling the story.

Take overdue loans. For all commercial bank lending to the private sector, the past-due loan ratio has dropped rather than increased, as it has in many other countries. It fell from 4.4 percent at the peak of the crisis to 3.2 percent in September 2011, according to Bank of Mexico statistics.

Take the soundness of the commercial banking sector. In August 2011, the capitalisation ratio for commercial banks was 16.2 percent, of which 87 percent was composed of highest-quality Tier 1 capital.

Or take liquidity, the dearth of which exacerbated the crisis elsewhere. By the common measure of average coefficient of liquidity coverage, Mexico’s financial sector exceeded 100 percent throughout 2011. The reserve coverage ratio of non-performing loans – a measure of banks’ exposure to suspect corporate debt, stood at 181.2 percent. From October 2011, banks started reporting their liquidity levels on a monthly basis under a template devised by the authorities.

Finally, inflation. Back in 2003 Bank of Mexico selected a three percent annual target and, despite potentially destabilising events in between such as record capital inflows and an expanding economy, that target has more or less held. Towards the end of 2011, it stood at 3.4 percent and was edging down to the bank’s long-standing goal.

And looking ahead, all banking institutions should be fully compliant with the Basle III capital standards as early as January 2012. “Since the current framework already includes certain components of Basle III, we do not expect a significant impact on the capital base of the banking system,” explains deputy governor Sanchez. Indeed with an average total capital ratio already sitting on 16.7 percent, any impact is likely to be soft.

Our winner

Mayra Hernandez and David Suarez, Grupo Financiero Banorte, accept the award for Best Commercial Bank, Mexico, 2011.

Mexico’s economy is set to grow by more than four percent in 2011 and 2012 – a significant increase over the last decade – as consumption and employment continue to recover well. Commercial banking in Mexico has performed well as a sector during those years.

Banorte’s Head of Investor Relations, David Suarez, explains how the bank is positioned to capitalise on the country’s below-average banking penetration; and Mayra Hernandez, Head of Corporate Responsibility, describes how Banorte’s growth path aligns with its CSR priorities.